人体肚脐发现数百新微生物

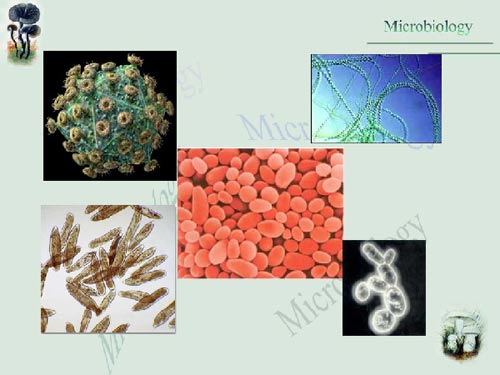

人类肚脐或许是微生物生长的一个良好环境,科学家在从志愿者的肚脐中获取DNA类型样本时发现了662种在以前的科学研究中未见过的微生物。这表明,人的肚脐为细菌提供了合适的环境。

英国《新科学家》周刊说,北卡罗来纳州立大学科学家开展的这个肚脐生物多样性项目分析了一大群志愿者的肚脐拭子。迄今,他们发现了1400个不同的菌株,其中近一半以前从未见过。

该项目原本旨在引起人们对微生物学的兴趣并减轻公众对微生物致病的担心,却同时获得了有关人类“微生物群落”——一系列生活在我们体内(和体表)的微生物———的新数据。皮肤仍未得到充分的研究,但北卡罗来纳州立大学的罗布·邓恩和伊日·胡尔茨尔领导的研究人员要研究肚脐是因为,肚脐比身体的其他部位更难擦洗。

科普作家卡尔·齐默和彼得·奥尔豪斯各自捐献了一枚拭子。奥尔豪斯的样本未获得菌落,但是齐默的样本显然充满生命。齐默写道,在他的微生物群落中,有一些种类以前只在海洋中找到过。还有一种称作墙壁圣格奥尔根菌的细菌只生活在日本的土壤中。

《新科学家》周刊报道说,研究人员记录下大量新的微生物,但它们大多数量不多。奥尔豪斯写道,大约有40种细菌占我们肚脐细菌总量的80%左右。

生物探索推荐英文原文:

Belly button biomes begin to blossom

The human navel should be designated as a bacterial nature reserve, it seems. The first round of DNA results from the Belly Button Biodiversity project are in, and the 95 samples that have so far been analysed have turned up a whopping total of more than 1400 bacterial strains. In 662 cases, the microbes could not even be classified to family, "which strongly suggests that they are new to science", says team leader Jiri Hulcr of North Carolina State University in Raleigh.

The project was conceived as a light-hearted exercise in science communication, but is making a serious contribution to the understanding of microbial diversity. Since New Scientist wrote about the initiative in April, samples of bacteria taken when volunteers swabbed their navels with Q-tips have had their "DNA barcodes" read by sequencing the gene for 16S ribosomal RNA, widely used in studies of bacterial evolutionary relationships.

My own sample was among 10 per cent of those in the first round in which reactions to amplify the DNA present failed - so the next installment of the comparison of my belly button biome with that of fellow science writer Carl Zimmer will have to wait for another day. Still, Zimmer has already been having some fun with his results, finding among other things that his belly button hosts Georgenia bacteria, previously found in Asian soils.

Results like this reflect our ignorance of microbial diversity, Hulcr suggests: the inhabitants of our navels seem weird because biologists haven't sampled sufficiently extensively to document the full diversity of microbial life in a variety of habitats. He likens reactions to the first round of belly button results to the astonishment of the first European explorers seeing African big game - which today seem commonplace. "Now you're expecting rhino and elephants," Hulcr says.

Also, identifying bacteria to species is difficult. Noah Fierer's team at the University of Colorado, Boulder, classified them into "operational taxonomic units" having 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequences that differed by 3 per cent or less. Apply this standard to mammals, Hulcr explains, and dogs and cats would be lumped together. It means that a "match" between a belly button strain and a species known from the deep ocean, for instance, may actually represent two microbes separated by several million years of divergent evolution.

Although the total number of strains recorded was large, the results so far indicate that a small group of about 40 species accounts for around 80 per cent of the bacterial populations of our belly buttons. "It is tempting to think of the abundant species as the good, core biome of bacteria and the rare ones as transients, struggling to take hold, sometimes at our expense," says Rob Dunn, author of The Wild Life of Our Bodies, and head of the lab in which Hulcr works.

Confirming that theory will require studies on a new scientific frontier: belly button ecology.