美国人的胃生来就不是给寿司预备的――至少一项新研究得出了这样的结论,科学家同时发现,日本人的肠道细菌所含有的酶能够帮助他们消化海藻,而这些酶正是北美人所缺乏的。此外,日本人最初可能是通过食用在海藻中茁壮生长的细菌而获得这些酶的。

Mirjam Czjzek并未对这种跨越文化的饮食习惯进行过比较。实际上,这位在法国布列塔尼沿岸的罗斯寇夫生物研究所从事研究的化学家一开始只是对如何消化一片海藻感兴趣。与陆生植物不同,构成海藻的碳水化合物“点缀”着硫分子,因此只有用特殊的酶才能够将它们分解。

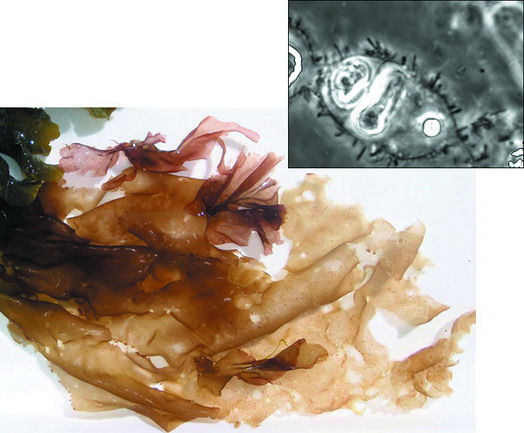

日本人――而非美国人――所携带的一些细菌具有一些能够分解海藻的酶,就像海洋细菌Zobellia galactanivorans(小图)一样。

为了搞清到底需要些什么样的酶,Czjzek和同事开始了她所谓的“在海洋菌类基因组中寻宝”的工作。研究人员将目光聚集在一种名为Zobellia galactanivorans的细菌上――这种海洋细菌已知能够以海藻为食。他们在Zobellia galactanivorans找到了5种基因,后者似乎能够编码一些可以分解海藻所含特殊碳水化合物的酶。当研究人员将这些基因转移到其他细菌上后,他们发现,有两种基因特别活跃。

Czjzek于是便寻思这些基因还有可能潜伏在哪里。她随后对有关细菌的海量基因序列进行了扫描,旨在寻找与两种Zobellia galactanivorans基因相匹配的基因,而惊奇也就随之产生。

Czjzek表示:“除了一个例外,找到的这些基因都来自海洋细菌。而这一个例外……居然来自于人类的肠道样本!”这种引起关注的细菌名为Bacteroides plebeius,它被发现仅仅存在于日本人体内。为了搞清这些酶是否为日本人所特有,Czjzek的研究小组将13个日本人与18个北美人的微生物基因组进行了对比。Czjzek说,其中5个日本受试者体内携带了这种酶,而在北美人中,“我们一个也没有发现”。研究小组在最新出版的《自然》杂志上报告了这一研究成果。

人类肠内有很多对宿主有益的细菌。其中一些能够分解人自身的酶无法消化的碳水化合物,从而让人们得到更多的热量。在日本,每人每天大约会摄入14克海藻,这些难消化的食物中的一些来自包寿司的海苔,以及很多汤和沙拉中的原料。

美国斯坦福大学的微生物学家Justin Sonnenburg认为,在人类历史上,吃进的细菌可能为肠道中微生物提供了很有价值的基因资源。作为论文作者之一的Gurvan Michel认为,西方吃寿司者不太可能得到这种能力,基因转移这种事情非常罕见,对于那些习惯了西方饮食的肠道细菌来说,消化海藻中的碳水化合物显得不是那么必要。而日本人却有着不同的饮食习惯,他们摄入更多的海藻,从而给肠道细菌们更大的选择压力,让它们保留消化海藻的基因。

美国康奈尔大学的微生物学家Ruth Ley指出,科学家之前曾认为消化道细菌能够从其他微生物中攫取基因,这一过程即人们所说的横向基因转移,“但是从没有一个实例像现在这般清晰”。他说:“我认为这是人类文化如何影响消化道(中的细菌)的第一个例证。”

《自然》发表论文摘要(英文)

Nature 464, 908-912 (8 April 2010) | doi:10.1038/nature08937; Received 9 November 2009; Accepted 19 February 2010

Transfer of carbohydrate-active enzymes from marine bacteria to Japanese gut microbiota

Gut microbes supply the human body with energy from dietary polysaccharides through carbohydrate active enzymes, or CAZymes1, which are absent in the human genome. These enzymes target polysaccharides from terrestrial plants that dominated diet throughout human evolution2. The array of CAZymes in gut microbes is highly diverse, exemplified by the human gut symbiont Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron3, which contains 261 glycoside hydrolases and polysaccharide lyases, as well as 208 homologues of susC and susD-genes coding for two outer membrane proteins involved in starch utilization1, 4. A fundamental question that, to our knowledge, has yet to be addressed is how this diversity evolved by acquiring new genes from microbes living outside the gut. Here we characterize the first porphyranases from a member of the marine Bacteroidetes, Zobellia galactanivorans, active on the sulphated polysaccharide porphyran from marine red algae of the genus Porphyra. Furthermore, we show that genes coding for these porphyranases, agarases and associated proteins have been transferred to the gut bacterium Bacteroides plebeius isolated from Japanese individuals5. Our comparative gut metagenome analyses show that porphyranases and agarases are frequent in the Japanese population6 and that they are absent in metagenome data7 from North American individuals. Seaweeds make an important contribution to the daily diet in Japan (14.2 g per person per day)8, and Porphyra spp. (nori) is the most important nutritional seaweed, traditionally used to prepare sushi9, 10. This indicates that seaweeds with associated marine bacteria may have been the route by which these novel CAZymes were acquired in human gut bacteria, and that contact with non-sterile food may be a general factor in CAZyme diversity in human gut microbes.