来源:BUSINESS INSIDER

BUSINESS INSIDER 是美国知名的科技博客、数字媒体创业公司、在线新闻平台,由亨利·布洛吉特(Henry Blodget)创立于2007年,并一直担任CEO至今。报道范围涵盖IT技术、产品、趋势、业内动态以及各个领域的新闻事件等。

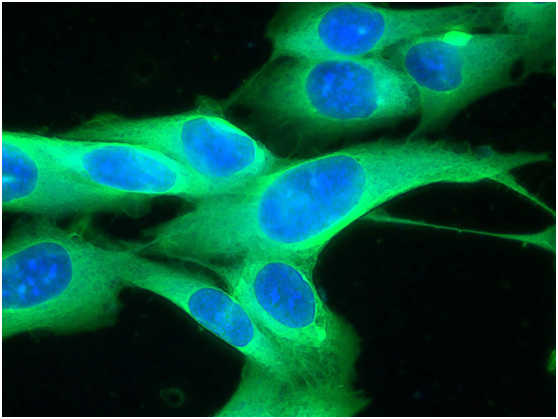

A human melanoma cell line

目前有两种最具潜力的癌症治疗新方法,一是免疫疗法,即利用人体自身的免疫系统对抗癌症;另一种是个性化医疗,针对特定患者本身的基因组和其癌症基因进行靶向治疗。

如今科学家们将两种方法结合创造出了一种全新疗法:针对患者个人开发出一种癌症疫苗,可激发人体免疫系统聚焦肿瘤发动攻击。

在初次的人体试验中,这种个性化的疫苗成功地激发了三名黑色素瘤患者的免疫应答。

这个治疗方法正处于早期研究阶段,至于它是不是真的能提高患者生存率或者在其他方面发挥作用,这时候下结论为时尚早。不过这个想法和临床的初次试验结果仍然让科学家们兴奋不已,而这个研究也刊登在了4月2日的科学杂志(Science)上。

在癌症中,每个肿瘤细胞都是独立的,这也是它们难以对付的原因之一。而这种新的方法就是针对了癌症的这个特点。那些引起肿瘤生长失控的受损基因“也会被免疫系统靶向攻击,以控制住恶性肿瘤。” 荷兰癌症研究所和华盛顿大学医学院的研究人员在同时发表的研究评论中解释道。

要建立这种个性化的治疗,科学家们需要先确定每个患者切下的黑色素瘤标本中肿瘤细胞独特的基因构造,然后对病人癌细胞表面的所谓“新抗原”这种特定目标进行识别。利用这些特异性抗原,他们为每个病人研制出了个性化的疫苗,来帮助激发他们的免疫系统攻击癌细胞上的这些特异性抗原。

分选出这些独特的肿瘤目标“有助于最大程度减少不良反应或副作用”华盛顿大学医学院基因组研究所研究员、研究合著者伊莱恩·马迪斯在接受记者电话采访时说道。这种个性化疫苗触发免疫反应的行为,表现得更像是狙击手而不是炸弹---因为利用这些抗原作为标记,它可以明确地除掉癌变细胞。

然而,这个过程很复杂:研究团队每研制一个疫苗要耗时近3个月---许多癌症病人等不起。研究人员希望通过完善流程来缩短时间周期至4~6周。

虽然这种治疗方法目前尚处于早期、不确定的研究阶段,但科学家们已经大受鼓舞,因为对于使用现有疗法都已失效的癌症患者,这种方法很有可能起效。这次的试验是针对黑色素瘤,科学家们迫切希望将其试用于其他与致癌物相关的癌症,如膀胱癌、肺癌、结直肠癌等。

然而,重要的是要记住,许多癌症治疗方法最初看起来很有希望,但实际并没有达到宣传的效果。

“这本不是一个治疗性的研究” 华盛顿大学医学院肿瘤学家、论文合著者Gerald Linette在接受记者电话采访时强调,“我们的首要目标是要确认这种方法是否安全,以及能否引发免疫反应。”

科学家们需要进行更多的试验来确定免疫反应是否与存活率相关联,以及在广泛的患者中是否可以被复制。

好医友编译

附英原文

business insider

The very first human trial of a new approach to cancer treatment has scientists excited

Two of the most promising recent approaches to cancer treatment are immunotherapy, which harnesses the body's own immune system to fight cancer, and personalized medicine, which involves therapeutics that are targeted to the genome of a particular patient and that patient's cancer.

Now scientists have combined those two strategies to create a novel treatment: a vaccine developed for a single patient that triggers an immune system attack that is laser-focused on that patient's tumors.

In the very first human trial testing this approach, the personalized vaccines successfully activated an immune response in three patients with melanoma.

The research is in its earliest stages - it's too soon to say if the treatment actually improved survival in the patients or whether it will work in others at all. Still, scientists are excited about the idea and the proof-of-concept results, which were published in the journal Science on April 2.

In cancer, each tumor is unique, which is one reason that they can be so hard to treat. In this new approach, scientists have used that to their advantage. The broken genes that make a tumor grow out of control "can also be targeted by the immune system to control malignancies," researchers from the Netherlands Cancer Institute and Washington University School of Medicine explained in a research review published alongside the study.

To create the personalized treatments, scientists determined the unique genetic make-up of each patient's melanoma tumors, which had been surgically removed. They then identified special targets, called neoantigens, on the surface of each patient's cancer cells. Using those targets, they developed a personalized vaccine for each patient that would hopefully encourage their immune system to attack these specific neoantigens on that patient's cancer cells.

Selecting those unique-to-the-tumor targets "helps to minimize adverse events or side effects," explained Elaine Mardis, a study coauthor and researcher at the Genome Institute at the Washington University School of Medicine, on a call with reporters. The immune response triggered by the personalized vaccines is designed to behave more like a sniper than a bomb - using the neoantigens as "flags" so it can specifically take out the cancerous cells.

Still, the process is complicated: developing each vaccine took the research team about three months - too long to wait for many cancer patients. They're hoping a timeline of four to six weeks will become possible as they refine the process.

Even at this early and uncertain stage, scientists are encouraged by this approach because there's a chance it could prove effective in patients who don't respond to existing treatments. And while the trial was in melanoma, the researchers are eager to try it out on other cancers that are associated with carcinogens, like bladder, lung, and colorectal cancers.

Still, it's important to remember that many cancer therapies that seem promising at first don't live up to the hype.

"This was not meant to be a therapeutic study," emphasized Gerald Linette, an oncologist at the Washington University School of Medicine and a coauthor on the paper, on a call with reporters. "Our primary goal was to see if this was safe and if we could elicit an immune response."

More testing will determine whether that immune response is tied to survival and whether it can be replicated in a wider variety of patients.